Loss of AE1

The Days Before

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) landings first occurred on 11 September 1914, at Herbertshöhe (now called Kokopo) on New Britain Island.

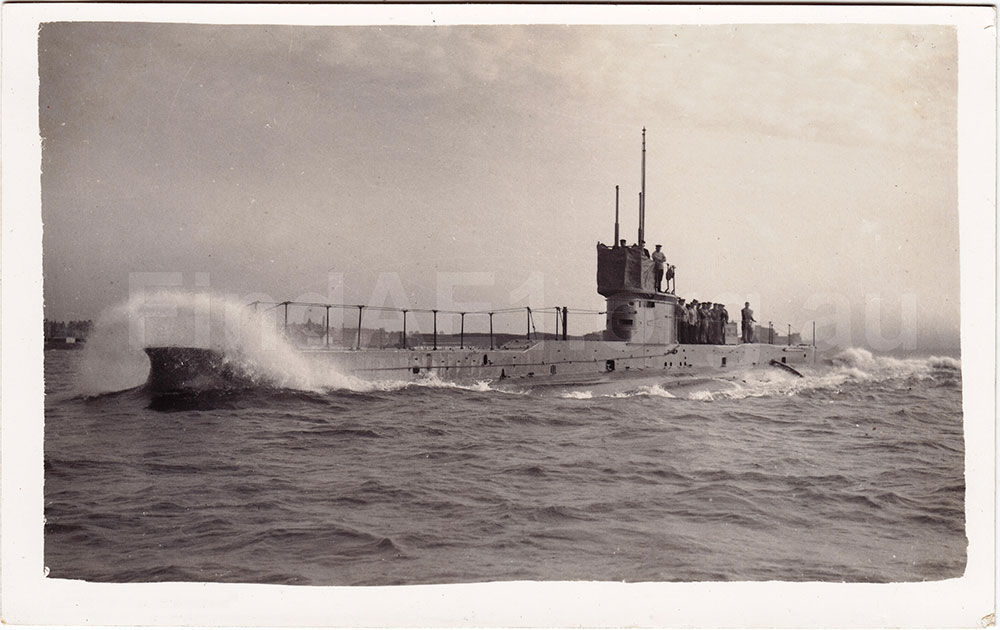

On the morning of 14 September 1914, whilst combat operations ashore were still continuing, HMA Submarine AE1 put to sea from Simpson Harbour in the company of the destroyer HMAS Parramatta.

Their orders were to stand out into the St George’s Channel between New Britain and New Ireland, to keep a watch for any German warships, which might come up and catch the invasion fleet at anchor.

A German cruiser squadron was known to be at large in the Pacific at the time and would have made short work of the invasion fleet if they had come upon it without warning, at anchor and off a lee shore. Subsequently, it was determined that the German warships were off Samoa at the time, but the maritime pickets were still a sensible precaution at the time.

A complete description of the events that led up to the invasion and the subsequent fighting and garrison activities at Rabaul and other places in New Guinea, may be found on the website of the Australian War Memorial, in the official Australian War Histories for World War One.

The Day of the Loss of AE1

The seas that day were calm, strong currents were running in the area, the sky was initially clear, although the day itself was hazy, with the visibility decreasing to about five nautical miles or less by 3pm that afternoon.

At 7am on 14 September 1914, HMAS Parramatta from Herbershöhe and AE1 from Rabaul left Blanche Bay together to patrol off Cape Gazelle. The ship and submarine patrolled separately for most of the day, Parramatta to the south east and AE1 to the north east.

At 2.30pm they were in communication and exchanged signals about the range of visibility. This was probably done by Aldis lamp, although both vessels did have radio installed. One diarist from AE2’s crew stated that the last communication from Parramatta was by megaphone.

Final Sighting

AE1 was last seen by HMAS Parramatta at around 3.20pm, in a position about 1.5 nautical miles to the southeast of Duke of York Island. Signals were exchanged about the visibility before Parramatta opened to the east; on losing sight of AE1, Parramatta headed back in the direction she was last seen. Parramatta steamed close to the coast but no trace could be seen of AE1 and the submarine was not sighted again.

Lt. Warren, Commanding Officer of Parramatta, considered she must have steamed back to harbour without informing him as she would have to leave at that time to arrive in harbour before dark. Warren’s report does not give a course, speed, or direction of AE1 when last seen.

We consider it most likely that AE1 would have set off to return via the shorter, southern route around the Duke of York Islands in order to arrive in Rabaul before dark as ordered.

At 3.45pm Parramatta stopped and remained hove too for 30 minutes before proceeding to round the northern side of the Duke of York Islands and thence to drop anchor at Herbertshöhe in the sharply falling tropical twilight at 7pm.

The Immediate Search for AE1

When the search for AE1 was launched, HMAS Yarra was on night picket duty, beating a line across the mouth of Blanche Bay between Praed and Raluana Points. She sailed out from her station immediately she was ordered to. Having returned to Simpson Harbour from Herbertshöhe at about 9pm, HMAS Parammatta proceeded to sea again to search with Yarra at about 11.30pm that night. Both ships spent the rest of the night searching the surrounding by star shell and signal search light.

The search was extended somewhat the following morning, with HMAS Encounter proceeding to sea from Simpson Harbour for about seven hours and conducting a search around the Duke of York Islands and to the northwest thereof, before returning to Simpson Harbour. HMAS Warrego, which was returning from a mission to Kavieng on New Ireland, also searched over a wide area, down weather and current from AE1’s last probable positions, basically to the north and west of the Duke of York Islands.

HMAS Encounter sighted an oil slick some 30 nautical miles to the northwest. It was not considered to be significant, however, and could have come from any of the warships that had been sailing in the area from the past several days (constant pumping of oily bilges was a common occurrence back then).

During the search on 15 September, HMAS Yarra struck a shoal in Foul Bay on the western side of the Duke of Yorks after proceeding through the Mioko Harbour passage. She damaged one propeller and also bent the shaft.

On the next two succeeding days, a collection of ship’s boats, steam pinnaces and small captured German vessels were employed on a detailed search of the coastline around the Duke of York Islands and along the northern coastline of New Britain Island. During the search of the Duke of York Islands, the local natives were questioned and they admitted to seeing the submarine during the day on 14 September, but had no further information about her loss.

At the end of three days of searching, there had been no trace of any oil, debris or bodies, and the search was called off. The fleet began to disperse to other objectives.

By this time, the invasion had been successfully completed and the tempo of the war was increasing elsewhere. All of the major war vessels were urgently required back in Sydney to refit and make ready to escort the first AIF contingent to the Middle East. At this same time, the German cruiser squadron revealed their location by a raid on Tahiti and the major Australian war vessels were sent off post-haste after them.

The Enquiry into AE1’s Loss

Vice Admiral Patey (the Flag Officer Commanding) carried out a rudimentary enquiry on the scene. His report ran to just several pages and concluded (based mostly on the evidence given by the captains of HMAS Parramatta and Submarine AE2) that AE1 most likely dived on its way back into port, to check its trim and/or clear a defect, and struck an uncharted underwater reef, thence sinking in the deep waters thereabouts. The report also noted that an internal explosion might have led to her loss.

Admiral Patey had to depart Rabaul in HMAS Australia and he left the continuance of the search in the hands of the captain of HMAS Encounter. No further formal enquiries into AE1’s loss were ever held, although Patey did subsequently submit two further reports on the matter to the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board in Melbourne. These were simply re-hashes of his first report, with no further new details being available to him.

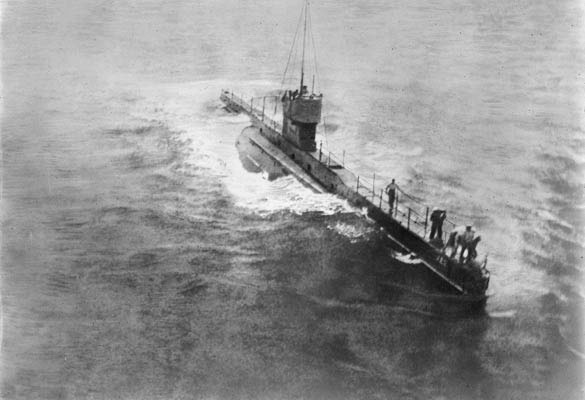

The Disposition of HMAS AE2 after AE1’s Loss

After AE1’s loss, it was determined that a single submarine was of less worth than her supporting ship elements cost to maintain. Accordingly, AE1’s sister ship, HMA Submarine AE2 was sent to the Aegean to join the British submarine flotilla at Tenedos, as part of the naval support element for the Gallipoli invasion during the Dardanelles Campaign. Despite attempts by several other British submarines, the AE2 became the first allied submarine to force a submerged passage through the Dardanelles, whereafter she ran amok in the Sea of Marmara. This had several historically significant outcomes. Firstly, her presence in the Dardanelles on that day caused a Turkish battleship, which had been bombarding the Allied landing beaches across on the other side of the Gallipoli peninsular, to withdraw. This had the effect of reducing the Turkish defences at the invasion beaches and may have had a significant impact on what was a very closely balanced day of action.

Overall, the Allied invasion caused great turmoil amongst the Turks, catching many of them unawares. Had it not been for the personal resolve of Kemal Atatürk and his military adviser, the German General Lyman von Sanders, Churchill (then the First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty and a member of the War Cabinet) may well have been successful in forcing the Dardanelles and relieving the southern flank of Russia, as was the British government’s intent.The other and certainly more significant outcome was that the submarine’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Stoker, made it through the Dardanelles and sent a signal stating as much to the ANZAC land force commander General Hamilton, on the evening of the first day of the Gallipoli landings. At that point, Hamilton was wavering about accepting the recommendation of his subordinate commanders ashore, who judged the assault and landings to be a failure and were urging withdrawal under the cover of the approaching night. Stoker’s message stiffened Hamilton’s resolve and he ordered his men to stay and ‘dig, dig, dig’, and thus began the eleven-month-long Gallipoli campaign. It was also the origin of the term ‘Digger’ to mean an Australian soldier. Thus it could be argued that the loss of AE1 had serious repercussions indeed.

Unfortunately for Stoker and his crew, a Turkish gunboat spotted AE2 as she attempted a second rendezvous with the British submarine E14, which had followed AE2 into the Dardanelles. As AE2 attempted to evade the Turkish torpedo gunboat Sultanhisar, she was forced to the surface, probably by localised strong upwellings of more dense salt water in the very powerful and mixed-up salt/fresh waters layers that exist in the Dardanelles. Once she broached, AE2was shelled and holed in the engine room by Sultanhisar’s 37mm gun. Stoker knew he could not dive again and as these early submarines had no deck gun, he could not fight it out on the surface. Stoker and the First Lieutenant opened the ballast tank vents and ordered the crew to abandon ship. AE2 settled into 73 metres of water off Karu Burnu Point and was not seen again until her discovery by Turkish marine archaeologist Selçuk Kolay in June 1998. All of her crew survived the sinking, but four of them subsequently died in Turkish POW camps before the war’s end.

After the war, Stoker was awarded a DSO for his actions and he later covered his submarine experiences in his memoir Straws in the Wind. The captain of the British submarine E14, Lieutenant Dunbar-Nasmith, was awarded the Victoria Cross when he successfully exfiltrated the Dardanelles and returned to Tenedos. Such are the fortunes of war. After the wreck of AE2 was found, several expeditions to the wreck site were organised by our colleagues at the AE2 Commemorative Foundation and the Submarine Institute of Australia. You can see more of the story of AE2 at the website ae2.org.au.